During the winter of 2003 Hylton Nel and Michael Stevenson had long conversations which were collated into this text.

Michael Stevenson: Let's start with an obvious question - when did the realisation dawn that you would grow up to be an artist?

Hylton Nel: At ten I was sent for a year to my father's old school in Beaufort West. For six months a same-age cousin and I boarded with my grandmother, a widow by then, living in the town. One day she asked each of us to draw a house and she would say which was the best. My cousin drew a very neat linear house and I drew a scribbly kind of house. My grandmother chose my cousin's as the best and I burst into tears. She tried to comfort me by saying, 'Never mind, you were not meant to be an artist'. This was no comfort because I thought I was meant to be an artist. So I just cried. Sending me away, I suppose, was meant to straighten me out, make me more bearable and reasonable ... and more manly.

Then at the age of about twelve I became friendly with a boy, Nicki Wessels, who lived nearby. He brought his elder sister's English poetry book from which we read with rapture. Using sheets for costumes we did plays improvising the words as we went along. By the side of an irrigation canal we built, in low-walled outline, palaces from mud inserting sherds of figured crockery for furniture. He said that in olden times slaves used to be built into the walls of palaces so we used the 'mad ants' that in summer run all over. We spoke about art and about being artists. By and by my parents decided his visits were too frequent and instructed me to see less of him. But we were not to be stopped, so we met in a strip of undisturbed bush at the edge of the cultivated land and continued our games of fantasy. Knowing him was important to me. At thirteen I was sent to boarding school. He ran away about a year after, anglicised, became a Roman Catholic and never never returned to that place.

And your parents' farmhouse, was that Karoo?

Not Karoo, no, both my parents came from the Karoo, but it was northern Cape, it was like Bethulie, deep in the interior. It was actually a very harsh landscape. Avenues of poplars which used to form a tunnel, a green tunnel - those trees were eventually cut down because they took too much water, so the crops in the adjacent fields would be poor because of these trees having taken so much water - so the trees got chopped down. It's a very harsh flat landscape between two low ranges, hills on one side, plateau on the other.

Did they farm sheep there?

My father farmed with cattle but that was on the plateau - so we lived in two places really. Cattle ranching - that was very romantic and very nice, sort of black earth and acacia Karoo I suppose - I don't know the names of the bushes - and nice rocks and things. Down in the valley it was red soil and wheat, peanuts, fruit.

And your parents' farm, and their farmhouse, what was in it that...

I'd say that in terms of something visual, it was my paternal grandmother who had some style, she always made gardens, and put flowers in the house, and had pictures and things like that - that would have been a real inspiration. She also made desert jelly from the joints of the autumn-slaughtered ox, which she flavoured with citrus and white wine. I have never known another woman to do that. Whereas my Ouma, who was a very dear person, but I don't know, I can't say how, but didn't have the style. My paternal grandmother, at the age of 90 (she was always a very slim woman) brought me a cup of tea in bed once, and she had a nice silk dressing gown, and she crossed her legs and you know I'd never thought of her legs and suddenly her legs were exposed, and I thought 'she's old but she still has legs'. But she had just a certain style, I think that was an inspiration.

And when you said you wanted to go to University to study art?

I think it was a shock for my father because when I was very little I'd always said I wanted to be a doctor, and of that the parents approved. But when it came to it, I realised that I hadn't actually communicated with them for years, because in Matric when they asked 'so what do you want to do', I said that, and I could see that my father was shocked, but he steadied himself and said 'Well, I won't stand in your way, but you must do all the applications, and if you fail, that's it', which I accepted.

Well that's very fair, quite supportive.

Very fair, my father was a very fair sort of person. From the age of about six until we sort of reconciled, I had from him harsh disapproval. He actually told me once he thought art was shit, an opinion, I am sure shared by many. We had years of very difficult relationship, but somewhere in my 40s we found some sort of reconciliation and some peace. We shared an interest in particular books, and it was nice to have that contact in a sense.

Your parents - were they well read and well travelled?

My father read - he went to North Africa and Italy during the Second World War, and he read. When he was a young person he read cowboy books and hunting books, but later on he didn't read fiction at all. One writer that interested us both was Wilfred Thesiger - I introduced my father to his writing, which he really liked.

And your fascination with literature?

I can't say where it comes from. My grandfather was an educated person, he started school at Bishops and finished school in Geneva and then studied law in Germany. Jan Smuts, I think, effected a reconciliation after the Boer War and then people came back to South Africa. One side of the family on my father's side went sheep farming in Argentina and never returned. On my mother's side I think it was much more … Several of my mother's brothers were doctors, but my Ouma, as we called her - I had an Ouma and a Granny - she was much more sort of rural, a simple country kind of person.

So in a strange way you are a combination of the ouma and the granny?

Ja. My Granny lived on a farm in the Karoo as well, but she had big gardens, all kinds of gardens, it was from her that I learned the names of plants. She would be up very early in the morning, and by the time you got up she would say 'you're only getting up now, I've been round the garden four times already', and then she'd say the names, you know : 'This is known as snapdragon but its proper name is antirrhinum'.

Then Grahamstown in 1961. Why Grahamstown? You could have gone to Michaelis School of Fine Art in Cape Town, or Wits in Johannesburg, or what were the options?

An art teacher of mine...

From Kimberley?

Ja - she had been to Grahamstown, and she was an inspiring person. And I had an uncle living in the Bedford district, which was convenient as I used to go there for short holidays, so I think that from my father's point of view, he would say that was the reason, because we had an uncle living in the district, you see. I discussed this with my father once - for me it was the fact that this art teacher that I had loved had studied at Grahamstown, and he insisted that the decision had been his and related to the fact of an uncle living conveniently near.

And when you got to Grahamstown - the whole sensibility of studio ceramics, had any of that filtered down to Grahamstown?

No. This art teacher had arranged for me to do evening classes on Monday evenings while I was at school, and those were very, very primitive and inadequate - strange sort of old lady affairs - but it just was an introduction. And then Grahamstown. There was a very nice man, Mr Hamburger, I think a German refugee, who'd come to South Africa probably in the mid-1930s. He made stuff, and provided buckets of glaze and things like that. A group of us used to experiment - we looked at Bernard Leach's potters book without actually understanding anything, because you know - the chemical component, we knew nothing about that, but we would read that and get fired up by it and then make mixes and put them on the things. Mr Hamburger wouldn't fire things if they looked funny, because he was scared they would damage the kiln, so we'd put stuff on, and then put a layer of his glaze that he'd provided over that, and in that way they'd get fired. We subsequently learned how to operate the kiln ourselves, and even used it for cooking food.

So, art education in Grahamstown in the early 60s was very much paintings, very sort of formalist - sketching, life classes, still-life studies, composition, perspective.

Our teacher, Brian Bradshaw, was a romantic and extremely passionate person, and this pushed one to some sort of edge, a more-or-less unbearable edge. It wasn't - it didn't feel tame in any way. The art school had a big cabinet with a very interesting collection of things - bits of Greek terracotta figures, and Chinese things - some American foundation I think had given money long ago - 1920s or something - for them to buy beautiful things for our art school. I don't know who bought these things, but they were there. There was a Tang dynasty horse, and a Song brushpot.

And did they teach with them, or was it just your own curiosity that led you to them?

No, it was just there, the cabinet was just there, and it was wonderfully open - the cabinet was there, the cabinet was not locked, so I used to take things home with me, and have them in my room and bring them back the next morning. The library also was similarly informal - you just took out books and used them and kept them for however long. Later on, as I think the student numbers increased, they had to get some better system going.

Was there sculpture, was that part of the curriculum?

When we first arrived, there were masses of casts of classic things which were object drawings for us and extremely tedious to draw. I think that fashions must have been changing, because after that these casts went down into the cellar, and we pretty well abused them. They're worth a fortune now, those sorts of things, but we despised them, except if we thought they were attractive we'd sometimes take some and put them in our rooms, the smaller ones. But sculpture, no, not in the sense that I understand sculpture.

And do you think your wonderful spontaneous line drawing comes from all these years sitting in the studio?

No, I don't think so. I've always found that if I try to be really serious I end up with a very boring result, so I think I've always been kind of frivolous in looking for the line of least resistance. I subsequently became aware of oriental attitudes, and there is a sort of concept of other power, of trying to get yourself into some concentrated state of mind, and letting this other power take over - I've used that.

You spent four years in Grahamstown. Did you have old-fashioned art history starting with the Greeks and finishing with Jackson Pollock?

Yes, very useful, starting actually with the cavemen - cave art - then the Greeks, Egyptians, Assyrians, all those people. Very, very useful, I found, because it gave one a background - stepping stones - which subsequently one could explore freely, as opposed to the more structured art history stuff that for me is a form of mind-fuck. I really can't stand it - it's very preconceived stuff that is quite specific and pumped at people and leaves one no freedom.

For imagination.

Ja. I really appreciated that old-fashioned background thing - the art history was as a support for the practical making of art.

And theory?

Yes. Professor Bradshaw used to give us a subject called Appreciation of Art, which I suppose was a sort of art theory, and the subjects that he dealt with would be whatever it was that currently interested him, because he was always looking into stuff. So we had this old-fashioned approach, from the caves to Pollock, on the one hand, and then on the other, he went into byways, but in a way that I found very stimulating.

And how contemporary - where did the art history stop? We joked about Pollock, but was there a sense of contemporary international trends, of pop art and of minimalism?

I think that by the time I'd finished, by 1964, I can't remember whether Pop Art had arrived - maybe it had, and if it had, we would have seen some. I remember at the art school there were people that painted pop images - that could have been a year or so after I had left. But there was no Bauhaus-style teaching - which was widely used in art schools at the time - and that is an important point.

After you had finished at Rhodes, Belgium. Why Belgium?

I didn't want to go to England, because I thought I'd meet too many other South Africans. I really did want to see something different. My French is not good enough for me to have gone to France, the Dutch can sometimes be a trial, and I thought that as Belgium lies between the two it would sort of partake of the two cultures, which in fact it does. And besides which, I really like the paintings of James Ensor, and, you know, there's plenty of those to see there.

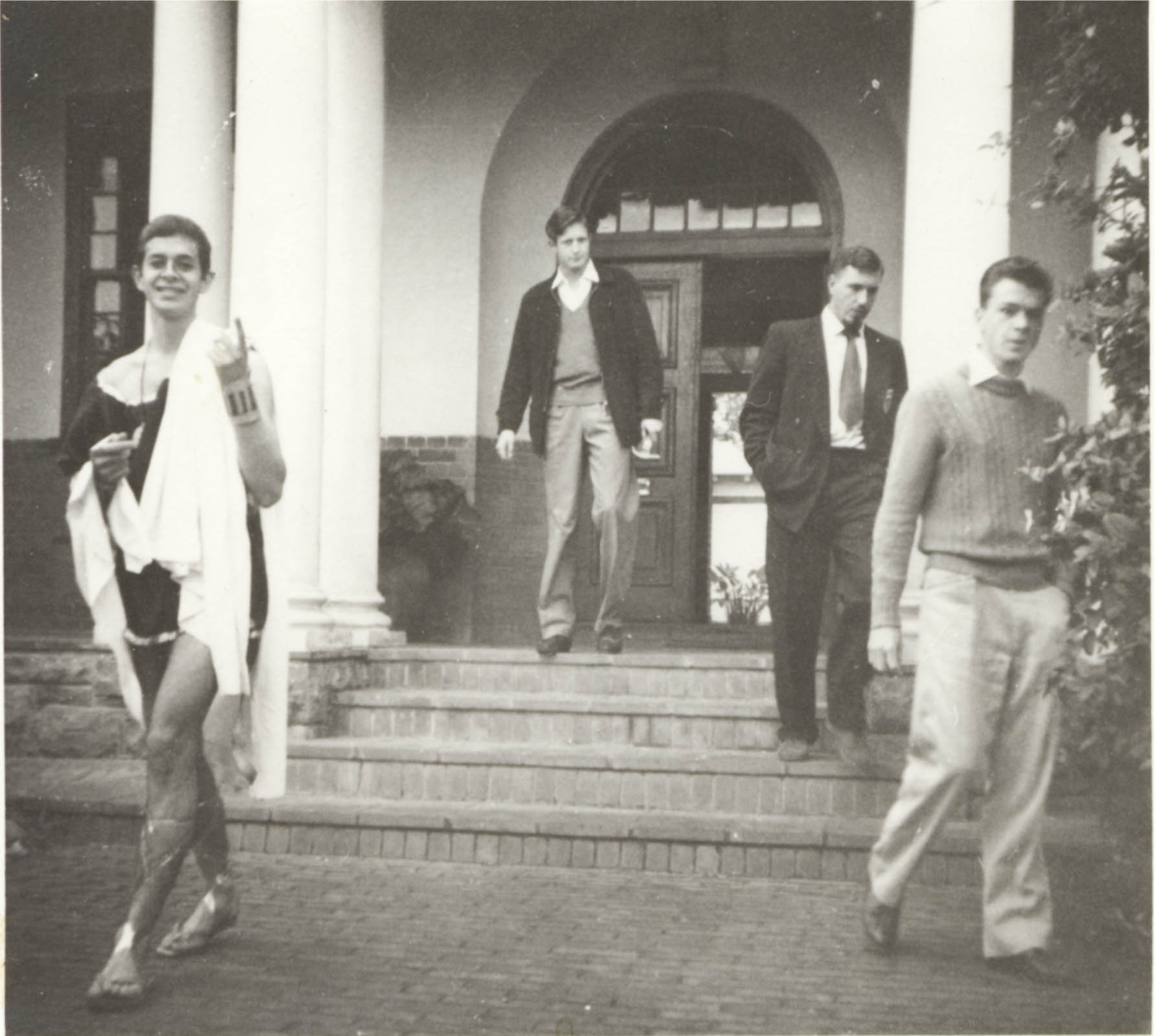

And the time at college there, was it an inspiration? There you were, a farm boy from Grahamstown, arriving in the metropolitan world. Had you hitch-hiked through Europe before that?

No, no, no - I came fresh! I came off the ship ... I mean I was so stupid that I didn't even know that you needed a visa to stay in a place - I just bought a ticket, a one-way ticket, and nobody questioned it. When I came off the ship they said 'Well, where's the visa', and I said 'I've come to study here for two years', and they actually let me off. I found a taxi, and asked the driver if he knew of a place where one might stay. He took me to the International Seamen's Institute, which was fine. I took a walk, and saw a Gothic cathedral for the first time, which was just amazing. I mean the dark streets, suddenly you had narrow streets instead of the wide open ones we have here. Narrow streets, dark buildings, and this Gothic cathedral - it was really impressive. But after about 24 hours the police came - the harbour police - and stood by while I put everything back into the suitcase, and then they put me back on the ship. I became the responsibility of the ship's captain, because I had to apply from a foreign country to get permission to stay in Belgium. I spent about four or five days on the ship, because they were off-loading or something. It was not very enjoyable because there were no other passengers, but I was the ship's responsibility so I was in First Class - wonderful food and a cabin all to myself and everything.

And from there?

I went to Holland, and then applied for a visa from there. I needed to do an entrance examination, which I did, and eventually it was all sorted out.

And studying there for two years - was it an extraordinary stimulus?

Yes, it was. It was very strange at first, and I found the language difficult, but eventually one understood where one's ancestors had come from. It was wonderful, I could go to museums over and over. There is a medieval meat-butchers guild building, which is a museum, and I just used to go there over and over and look, I just loved it.

And the actual teachers, were there teachers that were inspirational?

Ja, there was one person who was very inspiring - he was a painting teacher. But eventually I found it too difficult to paint, I mean I just found it too difficult - the light, just the whole difficulty I have with painting. I had a little period where I thought I just can't bear this, I've got to go back home, then it seemed like a waste of money, so I pulled myself together. There were three ceramic studios. I then became a free student. Having paid - I think it cost quite a bit, which they then refunded - I became a free student. I chose the ceramic studio where I thought I would be least bothered. A very good choice - I can't remember his name but he was a very nice man and he didn't bother me, I mean only if I asked him, then he would tell me things. For technical problems, he'd send me to another studio where the man could answer a simple question taking a whole afternoon, so I tried to avoid going there too often.

And the work you did in those years?

There were some nice things - when the period came to an end, the Director called me in and asked me what I was going to do with the things I'd made. Because of the physical difficulty of moving things, I said, 'Well, I'll take one or two and I thought of just leaving the rest.' And he said 'Perfect. If you do that, then I'll give you a good diploma.' And he gave me a diploma with distinction, because he wanted the stuff left at the art school, for whatever purpose.

So it's still probably lying somewhere in the art school.

Ja, probably scattered. I did go back years after, and they said 'Oh, you're the South African'. There were one or two of my things, and I took a few.

And what work were you doing?

I was doing sculptural things mainly.

Sort of figurines and ...

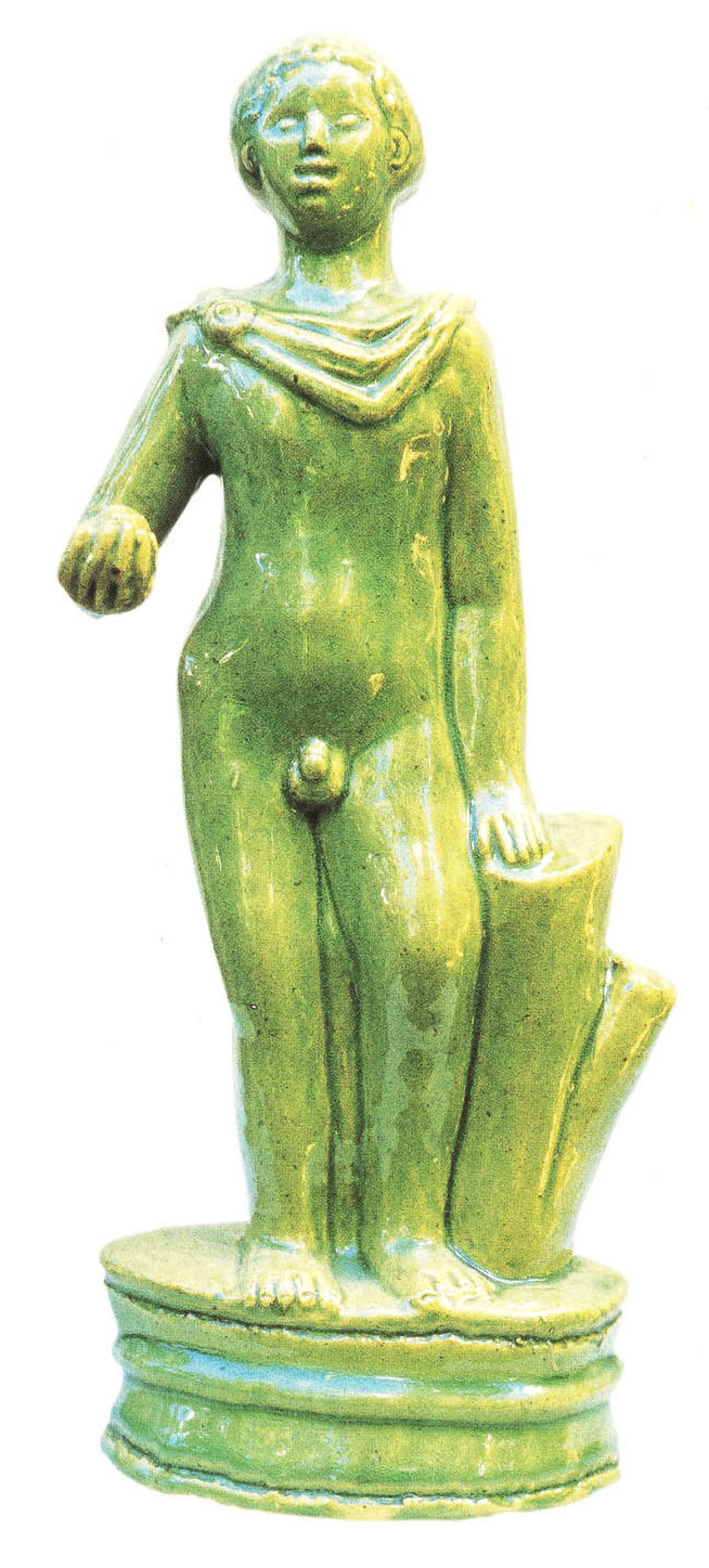

Ja. It was a long time before I made vessels. The sculptures were earthenware, and the school had coloured glazes, which one mixed in small quantities and laid on with a brush. So they were fairly multi-coloured.

You did the grand hitch-hiking tour of Europe in those years - the revelation of seeing the art you knew from textbooks in the flesh in the museums?

Ja, the Acropolis and all that in the flesh, after the casts in Grahamstown. Also, what struck me most forcibly was the colour of the marble. I'd seen it in the British Museum, where it's got cold, it's been in England for a long time and it looks sort of greyish. And in Greece it's got a - I suppose it's an earth stain or something, but it seems yellow, golden. And then there were the other things - there's two streams, Apollonian and Dionisiac, and the things we learn about in art history tend to be the Apollonian things, and the monster faces, and the snakes and things like that - they were there. No it was wonderful, marvellous to scratch about in the earth and find ancient fragments.

On these travels - any lingering memories of wonderful encounters or companion travellers?

A snapshot from those years taken by a photographer in some public garden in Athens of Ronald Kibble always brings back memories - he was the most brilliant hitching companion. A cousin wanted to go to Greece and we hitched, and somewhere along the line we picked up two hitchhikers - one was an American and one was this English guy, and the American moved off, and my cousin went to Turkey to have her last chance of getting hitched with a man. This guy and I, we decided we'd go about together, and we worked first in a youth hostel in Athens before going to the islands.

Were you lovers?

No, I liked him but we weren't. He was an electrician who worked on cranes, and he'd committed a certain number of traffic offences, and if you went over a certain number they would take away your licence for six months or something, and he couldn't afford that, so he had to get out of England. Knew nothing about art - nothing at all, but had a totally open mind. I didn't mind looking at the stuff that he wanted to look at, and he didn't mind looking at the stuff I wanted to look at. He never complained, only enjoyed. There is poem of his written in Beirut I copied into my journal from December 1966 which always brings a smile to my face:

As we drove through the night with the wind on our tail,

The engine ran smooth with not a sound to be heard,

only the tyres screamed hell with every turn

At every bend and mountain rise, the exhaust spoke forth with fury and might

Which made us drive on through rain and the hail of that black night

The cars we passed could not keep pace and during that night many said that

we could not finish the race

But we two knew that none could pass us,

For the chances we took we knew were great.

But the prize for not being late, was two beautiful girls in which layed our fate.

So you finished the two years in Antwerp, in Belgium. And then you moved to England in ?1969. To live? Where did you see yourself in the world?

I don't think I had any clear idea - I was young, and so you put one foot in front of the other. So I was in England, then came back to live with John Nowers. He moved from Cape Town and lived in a house that he had bought with inherited money in Richmond, Surrey, and I used to visit him there from Belgium. And then at a certain point we went back from England to South Africa - I can't think what prompted us to come back to South Africa, but we did for about a year, and then we left again. And when I left again, it was meant to be for good. But when our relationship broke up after eight years, I needed out.

So this is when you returned to settle in South Africa?

Ja, that's when I came back finally. I thought of going to France, but I got an offer of a job in Port Elizabeth, and I sort of just really needed to get out, and so I accepted it. That was a strange feeling, because I had in fact said goodbye to South Africa by then. But I've not regretted it, and from sort of a feeling of pessimism, I feel relatively optimistic.

We'll get back to Port Elizabeth teaching in a moment - let's just go back to the years in Britain. You and John were living there and running a little antique shop. And were you making things on the side?

Yes. Ja, that's what we were doing. We didn't have the antique shop to start with, I don't know how we survived, but we eventually got the antique shop. I mean I spent such a lot of time in antique shops that it seemed the logical thing to do, to maybe buy and sell. And we carried our work around in London, and tried to find markets for it, until eventually the - I think it was called the Craft Centre of Great Britain - said that they had sittings of their Board once in every three months, and you could submit, I think, six things. We were making mostly these rather colourful figurines - which were not pleasing to Bernard Leach adherents. They accepted the work and we sold to Japan and Scandinavia and people like that. It was extraordinary - when, after a long time, I had my first exhibition back in London, somebody who I didn't know at all who had bought things then, brought them to show me, and it was extraordinary to see things from then.

Made 30 years before! You tell a wonderful story about taking your work to the Contemporary Art Society...

It was the swinging sixties and women were coming into their own. It took ages to see the woman in charge, we had to wait and they kept saying 'She's very busy'- more-or-less saying 'I don't think she's going to see you' - but we said we'd wait, and we waited and waited. Eventually one of her underlings led us in, and there she was, perched on the edge of her desk doing her nails and blowing them dry. When she'd done that to her satisfaction she turned to these things that we'd by then laid out. She asked if we minded her being frank and of course we said no, and she said 'Well, you may think this is art, but I'm telling you now that it's not.'

Coming back to Port Elizabeth - you taught at the Port Elizabeth Technikon Art School form 1974 to 1987 - is teaching something you relish?

Ja. I mean I eventually decided that I didn't like teaching pottery any more, because it was taking too much out of one - you know, you get some idea and you share it with people and they use it in a way you hadn't quite anticipated but which also means you can't use that idea again.

It takes the energy out of one.

Ja. And so you would keep thinking of new things. In the end I found that teaching drawing, which is what I did at Michaelis in Cape Town and in Stellenbosch, was fulfilling, gave you energy, because a pencil mark doesn't fall off the paper, so whatever people do is alright, as it's their way of seeing. And that was energising, as opposed to the clay thing which is so bound up with its technique that you give all the time, and it's difficult to find space for you own work. After three years of Michaelis, more-or-less a year at Stellenbosch. And then I decided I'd had enough of teaching.

When you came back to Cape Town and Michaelis in 1987, wasn't John very much around?

Oh yes, yes. Life had moved on. We were friends again by then - I mean we had lived together for eight years, and that was some years on.

And John's work and your work?

I've never been able to look at John's work properly. I suppose there's something about it that's too close, or something, but I've never spent time with John's work, I'm afraid. Maybe we were just too close, or something. His whole feel for clay was completely different from mine. What he did was, I felt, completely different, and so it didn't do anything for me - it was not part of my thinking or inspiration or anything.

And - an integral part of your existence for many years has been Bernard.

Yes, we met about a year after I returned to South Africa in Port Elizabeth. Ja, coming on 30 years ago.

He painted beautiful paintings at one stage.

Yes - well he still does, but just if the spirit moves him - he just does it from time to time. He has also made some figures, portraits of dogs, you know, dogs that we've had, and things like that. And again, very different from my way of seeing, but I appreciate, I like what he does.

Going back to the rural life - you trod your own path, you always lived in these distant environments. Is that perhaps why your work is so distinctive, and can't be confused with any other ceramicists' work? As an outsider, is there a spirit of back-to-nature, an unhurried craftsmanship. I never look at your work and think of anybody else's.

I think that I feel that being queer, as it were, makes one ...

Individuated, or?

Well, you have a sense that in some ways you're not ... I've never felt pukka. It puts a kind of handicap on one's development, and one has to deal with that plus make a life. It seems to me that other people, more normal people, put it that way, just know what to do, and they just do it, and they create houses, and the kitchen works, and the laundry works, and the garden's there, and all that. I think that I have a very strong sense of having to construct this artificially, so I make a house, and try to get the laundry to work, the kitchen to work, but it doesn't always feel absolutely real to me. As I have grown older, however, I realise that it is as real as any other. One tends to see other people's lives as more effortless. Of course that is not necessarily true.

I'm not following, carry on.

I deliberately construct a life, a family - it seems to me that to more normal people this comes naturally. I don't think it really does, I mean it's too simple a way of seeing it.

But you think that's why your work is so distinctive?

Because I've had to fight - you know it's almost as if you're born crippled and you have to learn to walk - that's how it seems to me. And the more I become aware of the fact that in ceramic production, hollow wares are the main thing, and then figures and things are a by-product, and so I think that my work eventually echoes that sort of thing. It's trying to make one's own culture, a world within which you can operate. I find it satisfying to be able to eat off things I've made.

But living in an environment where there is very little stimulus or overt manifestations of so-called high culture - you can't go to the museum, or have coffee with an artist friend, you can't really go to the movies, you can't go and browse in a bookshop, but yet your work is so full of inspiration and references.

I have books, that's one thing I really like to have. Having books, getting more, becomes an unruly passion which needs to be controlled to avoid it getting out of hand.

So I suppose you've created your own private world or cabinet of curiosities?

Ja, so I can refer to things like that. I do have conversations with artist friends, as I'm having a conversation with you - I have such conversations, perhaps not as often as I would like, but then you could spend all your time conversing….

Books and literature - are there types of poetry that you feel ... or certain bodies of literature, or ...

I really like certain translations from Chinese - The story of the stone, or Dream of Red Chambers, which is the same but just has two different names - one of my favourite books. I also like The Tale of Genji, and related things like Japanese women's writing from around the eleventh century.

And in Western literature? Do you read much fiction?

Yes. In fact I think that if I want to get the feel of 18th century England then it's fiction that provides a point of entry. There are academic studies that people do, reconstruct, and that's useful, but I find that in the fiction from the time… To get a feel of modern China, I read translations of modern fiction, because there's inevitably something there that gives a feeling of the time, which an academic work couldn't do.

A passing observation: your objects are conceived in a rural landscape - a decade in Bethulie and more recently in Calitzdorp. You have chosen places that are small villages rather than remote farmhouses in the back of beyond - is it a desire to be part of a community rather than to lead a monastic and isolated life? Do you see yourself as part of a long tradition of artists who choose to live in a rural landscape that provides the reflective space and inspiration for their work?

Ja, it's ... well, I don't drive, and I have to be friendly with drivers

I never realised that!

Ja. I mean I grew up on a farm - completely isolated - didn't bother me too much either because I was busy with whatever you're busy with and ... but I don't drive, so I wouldn't like to live in too isolated a place.

Tell us more about village life and its relationship to your work - your work blossomed when you moved to Bethulie and Calitzdorp - surely there is a correlation?

For eleven years after returning from England I worked teaching at the technikon in Port Elizabeth, and in terms of my own work, fixing the foundations. I have never been a team player and I became fed-up with work conditions at the technikon. Besides, Port Elizabeth is a provincial city which does not mean that I dislike it. It has a remarkable collection of earlier twentieth century British paintings for instance. It was a relief to move to Cape Town, relinquishing the certainties of proper salary, medical care, housing subsidy, pensions, etc for a miserably paid job at Michaelis, but a richer experience all round. During that time our friend Moira Benigson suggested that I hold an exhibition in London to which I agreed. Maybe because she was a little Port Elizabeth girl she could leap in where others might hesitate. But she arranged a lovely exhibition at Christopher Farr's carpet gallery in Primrose Hill. She has given me an overseas market. Her support and encouragement have been a great source of inspiration. Probably in preparation for that exhibition, I stopped teaching and at last gave all my time to making ceramics.

On the way back from an exhibition in Johannesburg, we came almost by chance to Bethulie where Bernard's father lives. We spent a night there and something about the quiet country place made us think of moving there where houses are really cheap. Many friends in Cape Town thought us mad and I even explored the possibility of using a computer to mitigate what we perceived as the impending isolation. But its face was too cold.

After eleven years of work, gardening and meeting interesting people, mainly people travelling between Cape Town and Johannesburg, building a library with the help of Henrietta Dax, it was time to move on again. Finally the basic mean-spiritedness of the white natives of a small town in the deep interior had gotten to us and it was time to find a better place.

Calitzdorp represents for us a definite up-grading. Luckily I had earned good money with my fruitful years of work in the southern Freestate. We found this house on the 26th of January 2002, exactly eleven years after moving to Bethulie. The surroundings here are beautiful and after all the Western Cape is a civilised area. In a subtle way one senses it is more gentle.

To answer your question then, my work has blossomed from the time I took the plunge to devote all my time to it after long, though unconscious, preparation. I am grateful and think that a late flowering could be better than an early one and any flowering better than no flowers at all.

Something about the country appeals to both of us because of pleasant childhood experiences. Here we can take walks over our own ground to enjoy distant views of mountains and on the ground the amazing plants as the change with the seasons.

I think of myself - and many other people who collect your work - living very urban existences - pressured, demanding, and I wonder what brings us to your work? Is it the references to nature, to an unhurried craftsmanship? Does your work perhaps serve as a connection with a lifestyle and a spirituality that is lost in our city lives?

Maybe it does. I look at and have looked at a lot of pottery stuff in books, and in reality, mostly made by anonymous people, but coming from particular cultures, and made for particular purposes. I try to make objects as real as I can, and from my understanding of what I see, there has been the long tradition of this. I look at pots in detail, the bones, the flesh, the skin.

What I'm thinking is the gap between the cultures.

I not only try to make it real, I believe it is real, you see, and so I don't think of it in terms of art which you put on some sort of pedestal and label it. At the time of making and while it's with me it is just a real extension of one's life, as it were. It's been a long time of looking at stuff that comes out of cultures where stuff is born out of need, so I guess for myself I sort of re-create that. Needs at various levels, because I sell my stuff, so it's a living. I always dreamt about belonging to a culture where it would be natural to make things for the natural needs of people. I mean if I make a dish I like to try it out, and make some food and put it into it. Flower vases - as I told you, I have problems with earthenware because atmospheric pressure pushes water through it. If you make a cup, the water wouldn't go through, because there isn't the same volume, so the weight of atmosphere is less, but the bigger the thing, the more the water pushes through - very frustrating. But I am about to make flower vases that won't leak, I've made a pale blue glaze (good for the green of plants) to be fired at a higher temperature.

Have you thought of the enormous gap in distance and context between your work on display at the Fine Arts Society in New Bond Street in London, and where it is made in a little rural studio in Calitzdorp on the edge of the Karoo?

I think it's like that with every place where somebody's making stuff - I mean like this Afghan carpet - in what shed was it woven, and then by what circuitous route did it actually get to be here. So I think every place where someone's making something, is a far cry from the white spaces of a gallery - but I think the white spaces of a gallery are also very exciting, I think it's exciting to isolate things, see things. I get World of Interiors, though it's very expensive, but I subscribe to that because I find that looking at things refreshes the eyes, for me - you begin to see things differently yourself.

Also what you were saying earlier - your work is seldom austere or serious - there is none of that absolute reverence of form.

I love that, but I can't do it, so the stricter I try to be with form, the more it loses, for me. Some people can do that, I think it's in your nature, and so I've often... Coming to terms with what one does is like getting used to and accepting your own handwriting - you have to get to that point where you actually accept it and even enjoy it, you just accept it So...I can't work very precisely.

Even when your work is undecorated, the forms or the colours are spirited -

I think that mostly it could be because I enjoy what I do - I really do enjoy what I do. I find it frustrating when a glaze won't behave or this or that. I think that enjoyment possibly comes through.

But at the same time, there's a restraint - thinking of the colours you work with, it's a very limited palette. There's also tempering: almost no modelling in your figures, line drawings, script -

One of the secret children's games that I used to play on the farm - there was a spring that flowed into a pond where there were geese, and the geese used to hatch there and then you'd find bits of eggshell, and goose eggs have very nice white eggshells. I used to take a little box of watercolour paints and paint on these bits of eggshell and then arrange them in little places - I had different places - and then I'd say 'these ones have got those and those and those pictures, and those have got those' - and it used to be just a game. And so art school, with its formal aspects, was an interruption of that, in a sense - I was learning valuable new stuff, but the whole thing, you know, was sort of difficult, whereas doing that with the eggshells was just pure pleasure. And then I went to art school in Belgium after Grahamstown, and worked for a bit, and it took about ten years to free myself from those formal constraints and to get back to myself as it were.

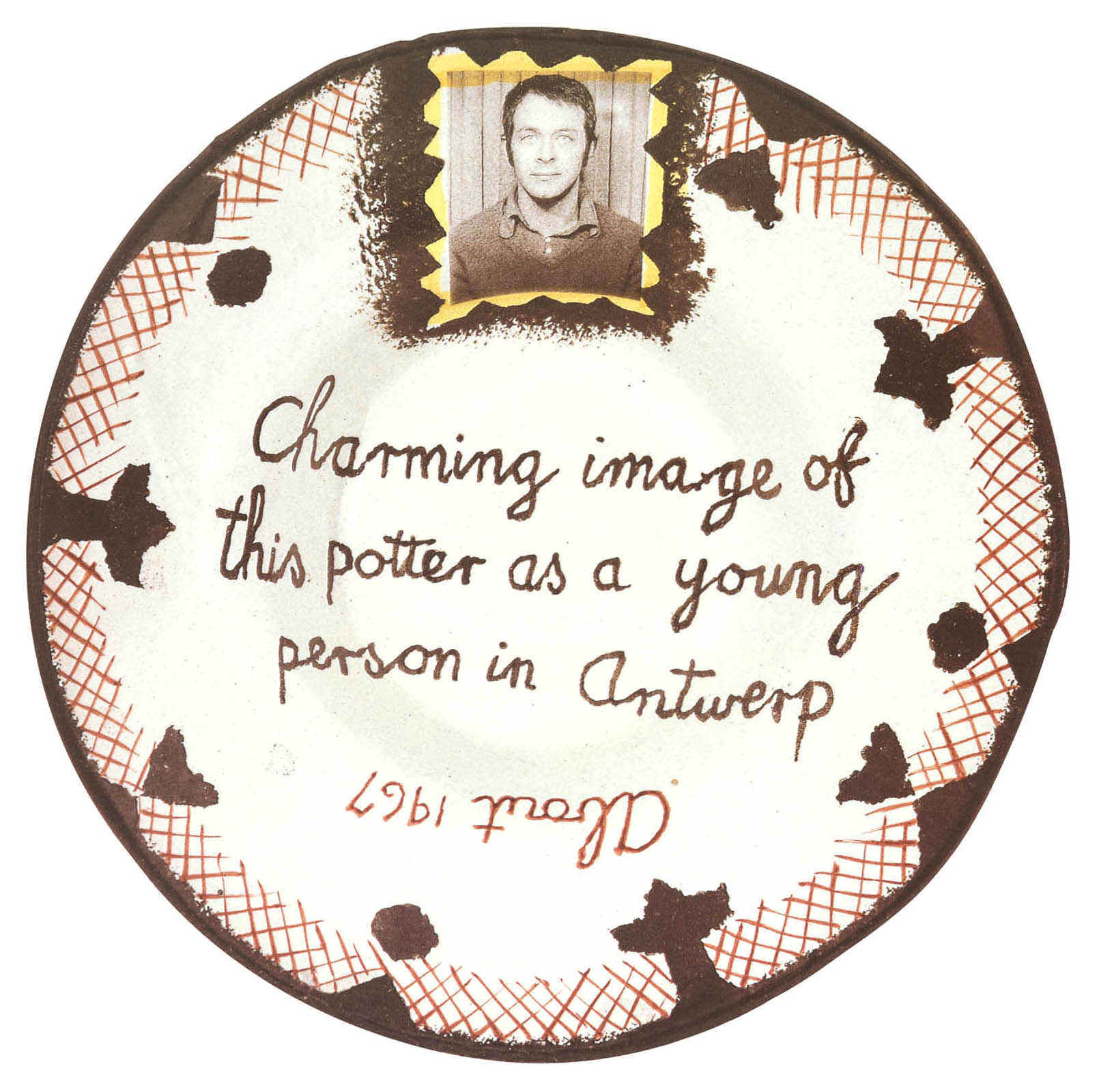

There is always an autobiographical quality latent in your work - in the last 20 years, at least, you have almost always dated your work to the day, which makes a fascinating narrative because so much of your work is made in response to the space and place in which you find yourself, and the fragments of art, literature and life which inspire you at the time.

Yes. But though I have through the years dated things it used to be sporadically. For the last about eleven years I have dated everything.

You're not spending 20 years trying to perfect a single form. I think that's for me what I find so interesting: it's your life history.

Ja. I think it's a sort of sense that each day is unique, and doesn't come back, and so I put my initials on a thing, and put this date, which is always changing, because time is passing, and even if the thing has no writing or no image on it, I know how I felt at the time I made that particular thing. So sometimes, if I've been depressed or something, there are certain plates - some of which I still have - which it pains me to use because I remember how I felt at the time. They just have a pattern on them, they don't have any...but for me the pattern has a kind of meaning that makes me remember how it was, and it was a bad time. For other people it just looks like a pattern, but for me it reminds me of that time, and the fearful preoccupations I had at that time.The autobiographical references are seldom direct, they are usually mediated with a metaphor from literature or art history. The references are there, to the good and the bad times, the loves of life and the death, the themes are there.

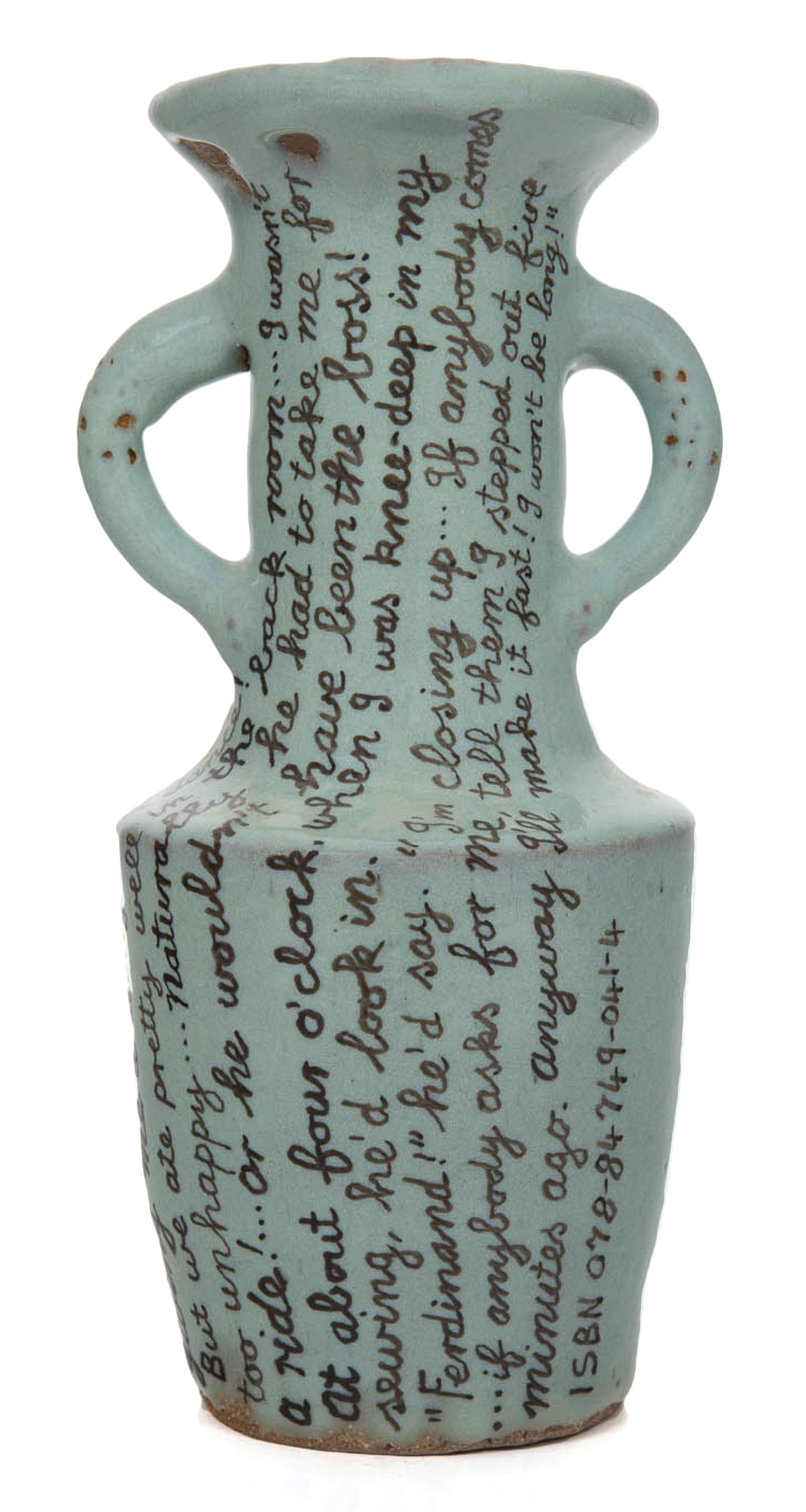

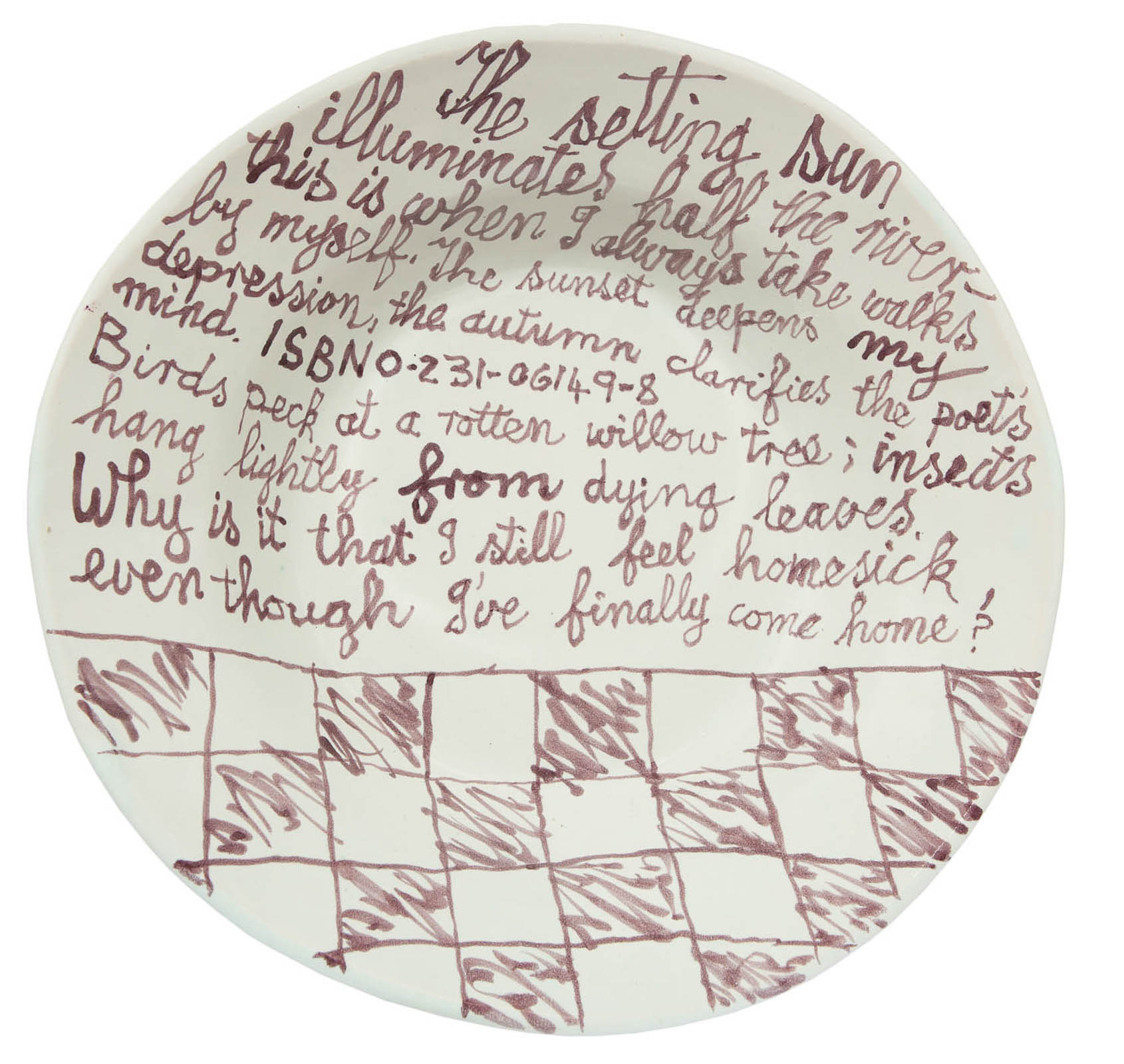

A little plate which you recently saw with the script:

'I shall go into a hare

with sorrow and sighing and mickle care

and I shall go into the Devil's name

Till I come home again.'

was a sort of protection for travelling to a place where I didn't really want to go, so it's like a disguise in order to get there and get back safely - it was made at such a time.

And I suppose it's not a conscious process?

No it's not - I mean I see it afterwards sometimes. After my father's death, the family house needed to be sorted out and I needed to go and get some things from the farmhouse. I didn't want to do it because there would be all sorts of disagreement and things like that, but I decided I really must do this thing, also because for memory I maybe wanted some things. Having made that decision, I had by chance been reading something - I can't think what it was, I think it may have been something about a writer, it was something to do with a writer who found that quotation, and found those words inspiring. I don't know where it comes from, it's in rhyming verse and it sounds like witches' talk, but I found those words inspiring as well, and so I used them. At a certain point I knew that they were necessary at that time.

To change focus - you seem not at all preoccupied with pushing the technical boundaries of clay and glaze, as your concern is the overall decorated form rather than a statement about the feats of craftsmanship. Your work is never self-consciously thin or huge in scale, always solid in structure, and modest, domestic and humane in function and form. Is this an extension of being an artist rather than a ceramicist?

I think the term I would use to describe myself would be artist/potter - I think that's an exact term. This use of the word ceramicist, or ceramist, which is the only one in my dictionary - maybe they've added the other syllable... The original meaning was someone who was versed in the technology of the clay, someone working in a factory or something, but it was when potters, people working with clay, wanted to be taken more seriously, that they coined these other words. People use the word potter and then correct themselves - I suppose you don't want to be called potter - but I think artist/potter is an exact description, and I think it's never actually bothered me, that sort of thing, because I've always known that if the thing's nice, it's nice, and it is some form of art. There is the hierarchy of materials - we know oil on canvas is serious, or bronze is serious, but I've always been quite content to work in this area which is not sort of serious in the way that oil on canvas, or bronze are.

And your thoughts about hierarchies in ceramics?

Ja, in my reading of things around Chinese ceramics (and they have a long history, a very rich history - they discovered porcelain and all those kind of things, and various glazes and things) there were different categories of stuff. There's stuff for kitchen use, there's stuff for reception rooms, stuff for a scholar's study, and then there's stuff in what's called Imperial taste. That often, especially in later periods, can become dry and boring - I mean very perfect, but in terms of the patterns they could use on that, you know, very restricted. And then you get peasant-ware, for the poor people, and you get stuff for the vulgar rich. I find all these categories interesting, you see, and I've never, never considered that I was working in the area of Imperial ware - but occasionally I privately venture into scholars' ware. There are discussions in my head. Few of my friends bother with the books I read.

I love watching people interact with your work, it's fascinating in that they instinctively pick it up, turn it around, look underneath, feel its surface, in stark contrast with so many ceramics which are intimidatingly precious - you're terrified to touch them, you admire them from a distance. Is this because your work is in many instances made to be used - they are practical, functional pieces, they're not objects of art that are easily fractured. My collection of your work stands as a testament to this, every day food is served in your plates and dishes, and your vases are often filled with flowers, and over a period of 15 years, perhaps two pieces have cracked or chipped through constant use.

Ja, aside from my leaking vases! But, the other thing - from let's say Chinese ceramics, let's keep it simple - is that Imperial vases, however perfectly formed they were, were meant to be both looked at and to be used, and I find that that makes sense. As regards a sort of untouchable quality, I think that comes from Western culture, high Western culture you could say. In a table setting, there is an array of knives and forks and things like that, and very flat plates usually, that could be some wonderful porcelain. And it sits there, and depending on what you could afford, I mean, you wouldn't even touch a plate - a servant might put the plate down in front of you and remove it again - and so this coldness comes with that. At a peasant level or Oriental level, which I'm not equating with peasant, the thing of tactility has always been important. Chinese culture is based on jade, and jade is a very tactile stone, and they use jade as a measure of things, a measure of quality in substances, and that makes sense to me, so I think that that is something that's in my mind.

In this age of perfect industrially produced forms, and in the era of Anglo-Oriental potters producing austere and distilled forms, your work has always had a rough-hewn, hand-made quality to it. Was this initially a conscious statement against prevailing fashion and taste, or... Everybody was making perfect things, but yours are always slightly wonky.

Well I just couldn't, can't make perfect things and if I try, you know, it's a form of torture, and I'm not going to get it right anyway, so that is what I mean by getting used to your own handwriting - just, you know, I couldn't make them perfect, but I still wanted to make them, and so I just make them - not deliberately distorted, they just come that way. My old teacher Brian Bradshaw used to say 'Make what you want to make. At first it won't be very good, but with practice it will get better'. That is the opposite to the Bauhaus-style exercises.

An interesting aside is that both your work and the Anglo-Oriental tradition share a preoccupation with functionality, although from two very contrasting perspectives.

Ja, I think that the Anglo-Oriental thing became more and more artificial. Just talking about the weight of something, I mean often those Anglo-Oriental dishes - and I like some of them very much, I'm not trying to knock them or anything - but they can be so heavy that they're kind of difficult to use, so that I try to make the plates not to be too heavy. The Anglo-Oriental tradition has few convincing flower-vases - a special interest of mine. They would put flowers in a jar or into a jug. You know the image, the hand-spun cloth, old brown jug, field flowers. I think that early English industrial pottery is just so beautifully thin, light, and I like that, but a lightness not in the sense of paper-thin, so that you dare not touch it, I mean it's just that it's actually easy to use, if it's not very heavy.

Another part of your work is the figurines and the small sculptures - they stand apart from your domestic wares. They're free-standing sculptures, on a small scale, and are a thread in your work that goes back all the way, from the early sixties through to the present day. You use the term 'ornaments' repeatedly, a term that unequivocally sets them apart from your user-friendly plates, bowls and vessels, and from the fine-art sculptures. You see them as sort of decorative objects?

Ja, you see, ornaments, I think, are necessary for the enjoyment of life - you need stuff to put onto the mantle-piece or whatever, so I actually like ornaments, and I think that... I mean I did a degree in painting and art history, and eventually found it very difficult to make something that would be just there for looking at. If I had to be thinking of that all the time, just making something just to look at, it would freeze me up and I wouldn't be able to do anything. And so, the work I do has different phases to it. Some of it is just absolutely mechanical, and by doing this mechanical part, it frees up the mind for later on, for maybe drawing or something. There are fewer figures, and I'd like to make more figures. I used to make only figures to begin with, and then these other things came afterwards. I'd like to make more, but I find it more frightening to make figures. I just, ja, I find it more frightening to do. But ornaments, in the house, in living space - one needs some. If you have a few serious things, it's kind of uplifting, but you need some ornaments for jollity, for, you know, interest, to pick up, turn around, look at.

If I read it rightly, looking at your work, there are almost two parallel styles - styles is a strong word - two approaches which you have in your work. One is a more sculptural, angular style, and the other is a more lyrical and poetic in spirit -

Yes

Do you sort of go backwards and forwards, or do the two happen in parallel?

Mmmm. They co-exist, I think, these two things. The very sharp angular things would be mostly things for looking at that don't necessarily have to be handled, and then the softer things are things like useful things, that I might want to have a softer feel. Or if there's a particular glaze I'm thinking of using - some sorts of glaze you can put on sharply angled things, which will cover and show engraved marks clearly. Other glazes may not be so easy to apply, and if you've cut a sharp angle they are going to make it too rounded, and it may not be very nice.

On a different subject, the tension evident in your early years between painting and ceramics perhaps only fused in the 1980s, when you started producing painted plates - the ceramics almost functioning as canvasses for your sketches, as a jotting pad for your passing thoughts.

It took me a very long time to understand. When I was at art school we were expected to make sketches, and then from the sketches a finished thing, and that was always very difficult for me. It's not any more, now I understand the sketches, I understand... For me, when you make a thing, that's it, you see, so I couldn't understand a doing a sketch preparatory to making a thing, but I've worked that out for myself now. And so the sketches are very rudimentary - little kind of notes - and then I use them to make a drawing, even if it's a simple line drawing. I used to do that more than I do now. Now I mostly just do it straight out of the head.

Continuing with the theme of painting ceramics - you studied so-called painting or art at Grahamstown, but at heart you were playing with pottery or ceramics on the side. Then you went to Antwerp, and there again you registered as a painting student. Was there was some sort of pressure, some sort of consciousness that one should be an artist, a painter, rather than be playing with pottery?

Yes

There's a tension in those early years that you had to work through.

Ja, the painting always felt very serious to me, and I didn't, to myself, feel a serious enough person to actually engage in it. I mean I just couldn't seem to. Maybe it just wasn't meant for me, so that pottery, which is something I taught myself basically, has always remained a sort of area where I felt free. So if somebody says something about pottery: 'no, if you do this, that', or 'you've got to do it like this' or something, I never... I check it out for myself, I mean if it interests me sufficiently, and so it's an area I feel is my own, and I feel free with it. You know, a lot of the things I make I don't like, and sometimes I have to destroy them and so forth, but that's fine, but it is my area. And so I don't look much at other contemporary potters' work, because it disturbs my vision, so I look just at these old things generally, or sometimes things coming from a particular culture, where you have a certain living tradition of stuff going on - that I find refreshing or instructive to look at. Recently, through the post, a friend sent me a 12th-century Korean celadon-glaze bottle, a very inspirational thing, a rough thing that has survived.

But I think the outcome of this - if I can use the word - tension, or this dual interest, depending on how you want to see it, both in pottery and in painting, means that in your work the decoration or ornamentation and the form is integrated in a manner that has few equals. It's a rare talent, because so often designs on ceramics do not follow the forms of the object, and they appear applied, where yours - the colour, form, design...

Ja, when it works, then it could be like that. I think also that drawing on a plate - it could be quite a mucky drawing, but it doesn't matter, because it's just a plate, so it also gives me another freedom - you see, it doesn't matter, it a plate, so, you can draw anything.

The points of reference and inspiration are multi-fold and generally historic. We spoke about the Orient - are there any more specific relationships you've had with bodies of work over many years, or things that you continually find yourself drawn back to?

Ja - I may have mentioned that I find living traditions interesting. I like classical stuff from the past, but I'm fascinated by living traditions which have transcended dynastic change, political change, and that still persist. So the Yixing teapots are interesting for me - just wonderful actually. And then there's a ceramic tradition in southern China, in Guangdong province, which has been ongoing, which was for ordinary people, and which appealed to educated people sometimes, but it was never an Imperial ware, the Palace didn't use it. I find their stuff amazing

And where do you get to see current or living…? Have you travelled in China?

No. There's some I can see in shops in Cape Town.

And you buy it?

Sometimes, ja. One of my favourite things comes from a Chinese shop in Pretoria - it cost R2 at the time. It's a little vase that's in the shape of a lion's head - sort of pale green glaze - I just think it's very nice and lively from Guangdong Province.

More specific references in terms of European ceramics - maiolica, Meissen?

Yes, because Meissen is a kind of Imperial ware - it was started by Augustus the Strong and so it was for kings and princes - and very elaborate, I do find early pieces very exciting. But that's not a source of inspiration specifically. Much more inspirational are the tin-glazed wares which in Italy and France were called maiolica, and in England and Holland were called Delft. It all comes from the same source - the Moors brought the technique into Spain, and it travelled from Spain to Italy, France and Germany, and lastly to England and Holland. That's a technique that I've been using for, you know - I've been using that method for some years.

English ceramics have been very rich for me, like Staffordshire figures, and then the whole Industrial Revolution, when Josiah Wedgwood re-organised the potteries in England and put them onto a really strong footing so that they could export stuff to Europe. English pottery wiped out the Delft pottery industry. That early industrial ware has a kind of tension to it that I think is very interesting.

Are there other painter/potters with whom you identify? I mean, Picasso, who painted on moulded work, is perhaps different to you because his forms and applied designs seldom appear as integrated as yours - a tough comparison.

Well, I find his work extremely seductive. For a long time I didn't look at Picasso's things much, because there was a time when I was at art school when Picasso's sculptural forms and pottery influenced me very strongly, but it felt too seductive, I didn't want to be seduced. You know, it could be easy to become a Picassette and I didn't want to do that, but now I find I can look at his work quite easily, and enjoy it.

What do you make of it?

Well I find it interesting, it links up with his sculpture, it links up with his paintings. I find it a legitimate and interesting aspect of his art. I once met a cultured man, a German Jew, with lots of books, some plants, no paintings and three objects: a copper-red Chinese vase with a curious history, a Meissen Comedia del Arte figure and a Picasso bowl. It struck me that there were no paintings and so I asked him about these three things. And he told me. Very instructive. I must clarify. I saw a Chinese vase, a modern bowl and what looked liked a nasty shepherdess figure. He explained what they were and how they fitted into the world of art. A revelation.

And historically, the line drawings on Greek vases spring to mind, not only in terms of style but also subject matter.

Ja, the techniques that the Greeks used on the classic vases were actually very, very difficult, but...but ja, I do...those lines, I think, are very nice.

And other painters, say David Hockney, who also has contemporary delight in the male body, someone like Robert Hodgins who is rich in literary and visual references. Do you have painters, dead or alive, that you take as points of inspiration...

I look at line drawings, especially painted Buddhist caves, tombs, but many places where there are brush-drawn lines.

... or do you keep going back to ceramics, historic ceramics, as your points of departure?

I think so, mostly - there's a little vase I made with a woman sitting on it - that image came from a newspaper advertisement for a massage parlour, a strange little image of a woman, and that was the inspiration for that. It reminded me of a picture called La Derelitta by Botticelli. Picasso is a different artist because he plays between drawing, sculpture, painting, ceramics, all that, so I've made things deliberately, a sort of homage. But no, I don't actually look at other paintings in terms of wanting to find references for my work.

And then the recurrent themes in your work, your idiosyncratic manner, the script on the ceramic forms, and treating ceramics as slates for passing thoughts and observations, and quotes, often not referenced ...

Well there was a short period when I used to give the references, but then as soon as you do that it makes it look pedantic and comes between you and the actual words. And so, I've always hoped that whoever's words I'm using - most of them could be dead - wouldn't take it as disrespectful that I don't say where they come from, because the words themselves have impressed me, and so I like to just put the words there, so that you have a straight response to the words. Maybe some people could find out if they really wanted to or I would tell them where the words come from, but...

And the historical precedents?

There are plenty of precedents for this writing on ceramics - it goes all the way back to Greek things, Greek vases have such writing on them, Chinese things have got such writing on them - you know, English things, Continental - it's always happening.

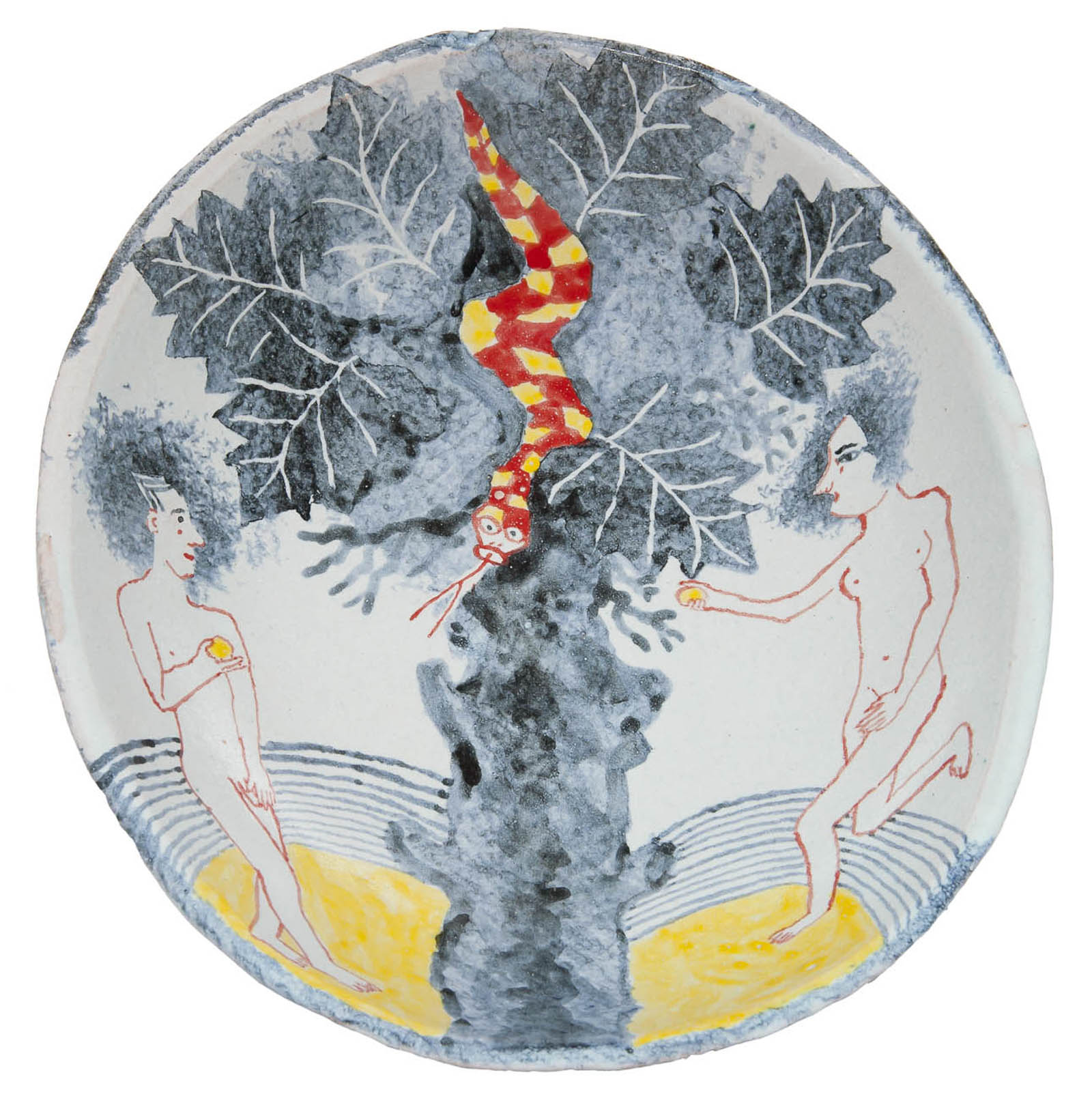

And the Christian iconography, the Madonnas and Child, the Adams and Eves, Christ on a cross - is this related to a personal spirituality, or is it just popular imagery?

It is, it has a certain resonance. You know, I grew up in a Christian culture, largely sort of Protestant, though I was confirmed in the High Anglican Church, which I found preferable. I mean the bleakness of Calvinism is something that I find intolerable, I can't live with it, and so I prefer to have images, I like images, and spirituality is so mysterious, so I use those things and without being able to say exactly, you know, this means that. They do have a spiritual kind of thing for me, without being specific.

Is there a childhood Bible with pictures that are still in your head that...

The childhood Bible that I grew up with was so awful, it was called Through the Bible by Theodora Wilson Wilson, and had photographs of archaeological things. I suppose if I looked at it again - I don't have a copy - I would see it differently. But when I was little, my father was in the war. My mother used to read us stories, just stories, children's stories and things, which we thought were lovely. And when my father came back, I suppose that he felt that he'd lost contact with us in a way, and wanted to get back some sort of contact, and so he took over this thing of reading for us. But no longer the lovely little stories my mother read, now it was Through the Bible by Theodora Wilson Wilson - what a name - and we used to get bored with it. And then he would get cross, you see, and demand that we pay attention, and we just found it utterly boring, because there was the sense that you ought to, whereas the stories my mother had done were just... just stories. I remember a lullaby, Babes in the woods, about the robin covering with fallen leaves the two little lost children asleep on the forest floor, while my sister and I lay in our beds, covers drawn to the chins.

So the iconography?

Sorry - in retrospect, I see that it was my father trying to make some sort of contact with us, but it didn't work too well, which must have been distressing for him, because he knew we didn't like it.

Another thread through your work is the male nude and other homo-erotic imagery - these themes, obviously an extension of one's own sexuality. At what point did art and this aspect of life become entwined - were you drawing naked boys as a teenager? Or was it only as your own consciousness of gayness dawned that your imagery reflected an admiration with the male physique and engaging with the energy of sex itself? And your imagery has become increasingly bold in this respect, perhaps a reflection of the times we live in, or...

Or just me getting older and maybe remembering joys receding. Must be careful not to do too many - but, I just draw people, whether male or female, they don't always for me have a sexual connotation, but drawing them naked seems to me the most basic way to draw them. I sometimes - I more often put clothes on women - the Greeks did the same thing - because I suppose that their naked form doesn't interest me as much as the naked form of a man. But even drawing naked men, it's not always for me sexual, I mean it's just like a human creature, and because of the awkwardness of my drawing they rarely look very attractive. Every now and then I manage to get one that looks a bit glamorous, but when they don't, I think 'well, I mean, who's glamorous'. I mean some people just look like they look, you know.

And your penises on plates, can you imagine at Rhodes, 40 years ago, thinking you'd be doing penises on plates - your professor would have had an angina attack.

No, he was too tough for that. He would have chased one out.

Obviously it evolved...

Ja, ja, and really, unless you're in a particular mood, it's uncomfortable to eat off a plate with something like that on it- you know what I mean. But there could be times when it could be appropriate, but mostly not, not for using, for eating off plates - I mean the plainer they are the easier it is, because it doesn't interfere with your meal.

And any sort of conscious links between gay liberation and the changing times and your imagery, or...

I suppose so, but not consciously. Gay liberation for a lot of people evokes images of parades of screaming queens. Not for me. But at another level I feel rage at the deep-seated animosity that's out there against queers.

Getting more domestic, the cats, the dogs, the flowers, the fishes - an extension of interest in food and gardening, daily world around you.

Ja, ja.

And social and political comment - statements of the time and place in which we live - a white man in Africa who deeply identifies with Africa, slips effortlessly between English and Afrikaans, who has lived in Europe, lived in Africa. There was a time when your work was very pointed, specifically in terms of South Africa.

Yes - I'm very happy to be living in Africa - with all its problems. There were times ... When I went to live in England it was a conscious decision, but I want to get away from all that, I don't want that anymore, and indeed, one felt freer there, because when I came back from England to teach in Port Elizabeth it was very obvious to me that there were certain subjects which in England I could talk about, to do with politics or something, and which here would be impolite, so that we did a certain amount of self-censoring. This kind of interested me, but I never... I don't actually think about that so much, but, ja, the thing of an exotic sort of white person in Africa - we've been here for a long time...

The many decorative devices - we keep placing emphasis on issues of line drawing, the illustrative imagery, but your work is so rich with re-interpreted geometric chequer-board designs, grids, triangular and circular markings, serrations.

Mmm - one of the interesting things about ceramics is that traditions have always borrowed from each other quite freely - when a new pattern sort of comes - it's also another aspect of the freedom I feel with it. And these things, hatched or zigzag or whatever, they are just so ancient and basic, and so you use them, and sometimes they work better than other times, and sometimes the line thicker, and sometimes the line thinner, and they're just things that you use. You just keep doing it over and over again, and sometimes it works better than other times - sometimes doesn't work at all, but ja.....

And the encyclopaedic range of art and literary references that circulate in your mind, drawing unexpected associations, often using this material as metaphors for your stance on the nuances of ceramic history or on the world at large - the way you so effortlessly combined willow-pattern with a Madonna figure ...

Ja, well you get that on Chinese export porcelain. A willow-pattern on a stag - I've got a picture of a willow-pattern, completely covers the figure of a stag - they are ornaments and they're meant to entertain and brighten up a place.

Let's focus on your collecting, and your collection, because it's an integral aspect of your creative process, and the breadth of your collection is reflected in the diversity of iconographic and stylistic references in your work. Your collecting almost provides references for your work, a 'study' collection at hand with an array of sources.

Ja, because I've got lots of books, with pictures, and as I've got older I've got more and more books, and with modern technology the pictures are more and more amazingly real. But a picture finally can't give you all the information you need, so I've got to have some examples of things, which are usually quite humble examples because that's what I can afford. They may be damaged, which again makes them affordable, but just contact with the real thing is useful to me - I wouldn't be able to get it all from books.

And as you say, your collecting is not for the financial worth or condition, rather points of departure gathered side by side, in bookshelves but not isolated, celebrated pieces.

No.

You're not a specialist collector focussing on a field or a period, in terms of ceramics - everything from oriental pieces through to Staffordshire, European maiolica, lustre wares, and sculptural pieces from many cultures, including African art. The internal logic is just pieces you respond to?

Ja, or what you happen to come across on a particular day in a particular place.

And your years as a dealer in England in the early 1970s, and later in the late 1980s in Cape Town - there's nothing like dealing to sharpen your sensibilities, because your living is dependant on your specialist knowledge and your responses. I know for myself as a dealer that it's about relationships with objects - you buy something out of curiosity and you can let it go when you have internalised it. I'm just trying to see whether there are linkages, which there must be, between your years as a dealer and between your own collecting and your own work.

Absolutely, because if you are dealing, if you're looking at an object, say a bit of ceramic, you turn it over, you look at the bottom, you look at it all round, because you're trying to establish whether this is a genuine 18th century thing or whatever it is, and so there are certain things you look at that would give you that information. And so in making things, one tries to make them so that they can be looked at all round, and this and that - it's to make it real. I think it does sharpen - it sharpens everything, it sharpens your sensibility to deal, to buy - I mean if you buy stupidly you're going to lose money. When we closed the shop, there were a few things we liked but nobody else seemed to. So we brought them home.

Exactly. So you have to learn, you learn very quickly.

Because you put your money there, you haven't only spoken about it or theorised.

A few technical points - the plates are made on a hump mould. And the cats and other forms, are they?

Press mould, so it's a sort of hollow form - whereas the hump is a convex thing the other is concave. And then, for a bowl, or plate, what makes it work is the hollow inside of it, that's the actual bit that makes it what it is. Whereas if you're making a cat, it's the outside, so I use a press mould for a cat and a hump mould for a bowl.

And clay - have you a long relationship with similar sorts of earthenware?

For a long time now I've been doing earthenware, and because the vases leak so fearfully in earthenware, I think I must make the vases at least.... at least fire the body to stoneware temperature. But - long relationship with what?

No, just what...have you had particular clays you've always ...

Oh, I've used a variety of clays over time, and I use what I find available. At the moment I'm using clay from Cape Town - I started using it before I left Bethulie, because the one supplier in Bloemfontein was getting very sloppy with the clay that he was providing - it had all kinds of things in it, and in other ways was not very nice to use. You know, I got tired of it, so I use clay from Cape Town. But I also sometimes like taking clay from where I am, because there's clay all over, it's just that it takes time to get all the little stones out, and then to test it to see whether it will work.

So when you say clay from Cape Town, clay that you bought from a supplier in Cape Town rather than Cape clay?

Yes, I guess it would be Cape clay, but it's very rare that a clay that you buy is just straightforwardly from one particular quarry. People often combine it with other clay or other things, and test it - so someone else has done that, and decided that this is workable clay. And this clay from Cape Town at the moment is ... I'm very happy with it, it's a very tolerant clay - in other words, in modelling, in adding bits on to it, it's plastic.

And glazes - with a lifetime of experimentation ...

It's not really a lifetime of experimentation. I use glaze in a fairly narrow range, and I got the recipe first from Hamer's Dictionary of Ceramics. I decided at a certain point - I was still living in Port Elizabeth - that tin glaze seemed fascinating to me, I do like the texture, the physical quality of it. Then Ian Calder, who lectures at Natal University, gave me access to their collection of glaze tests and recipes. The course there was started by a woman Professor Ditchburn and she got the recipe from Dora Billington, who was I think at the Royal College of Art. I use a sort of modified version of this recipe. You put so much of that, and so much of that, and as you weigh it out you mark it off. But, it's all white powder, and one day I was making that green glaze that gave me some problems to start with, but it came out. But there's a certain substance that I had to add, and I was listening to the radio at the same time. The ingredients are all white, and I found myself - because you weigh, you weigh, ok that's enough, and then I've still got some in the dish and I just put it back in the packet where I got it from - walking to a different packet. You see, it's all white powder, and then I think 'now did I take that from that packet or did I take it from where I was supposed to take it', but I don't know. You have to be very together, to be checking and double-checking.

And pigments?

The different way that the drawings come on the things often has to do with the pigment I'm using - with how it actually flows, because remember these things are painted on a raw, glazed surface, so it's powdery. Different pigments flow or don't flow - sometimes they don't flow, and so you struggle with the brush to get the mark made. And then sometimes it flows easily and if everything works.

And you never used the wheel?

I do use the wheel - it's my work station, a traditional kick-wheel - but not much. A fast wheel for throwing pots doesn't come natural to me. Some people can throw on the wheel and it's beautiful and they can just leave it and that's fine. For me, I mean I do use the wheel occasionally, but always, in order to make it mine, I use a knife afterwards, I modify the shape in order to make it my own, otherwise it just looks mechanical.

And relationships with collectors of your work - in my experience people do not own one or two pieces of your pieces, they develop a relationship with your work, and they follow every twist and turn, as a development. Even myself, as a dealer, who sees amazing things every day - I never cease to be amazed or seduced by your work, I find it irresistible - the rich references, the acute aesthetic sensibility. ... Many of your collectors you know personally.

Mmm. Ja, there are some that I don't know, which is nice too. I really enjoy relationship with collectors. As I said to you earlier, if people make comments - say they like this, they don't like that - I find it very useful, very instructive. And I find it extremely flattering, obviously, that people actually like what I do, and I get paid for what I make - I find that very, very flattering.

Are you ever conscious of thinking, while you're sitting working, 'Well, will this one do that, or am I pleasing this one, or...'

Ja, but you can't think about it too much because it could freeze you up. Sometimes if I'm asked to make things with a particular text or something, a particular commission, it's often very difficult. You know, you write particular things on there and if they don't like it, I mean there's nothing else you can do with the thing, because what's written on there relates to them, so that I find quite difficult. It would be different if I was working with particular colours at a particular time and someone comes and says.... It would be easier if they could say 'OK, I like this, this that' you know, 'in this colour that you're doing now - just write this and that', and that would be easier, but generally it's sort of more open, and so it's more anxious-making, because you've got to choose the colours, or whatever, you know.

Last thoughts about inspiration...

Ja - Bradshaw said you should always be at your easel, so that when the inspiration comes you're there to use it. You shouldn't be, say, in a car travelling to there or there, or way out in the veld or something. So you're there, because inspiration doesn't come all the time, but when it comes, you must be at your workplace, so that at least sometimes it hits when you're there. Because you can't recreate it, you know sometimes when you get brilliant ideas while you're travelling in the car, but once you get home that has largely dissipated. Do you find that?

It's like dreams - to recall them one need write them down immediately and analyse them soonest because by tomorrow you can remember the narrative, but the energy of the dream is gone, and you can't...

The energy is gone even if there are notes.

But the energy goes very quickly, as hard as one tries to retain it.

Ja, that's exactly how it is.